Teenage nutrition: the importance of a healthy diet in adolescence

Teen years can be tough. Not only do young people have to cope with the pressure that comes with multiple social media platforms these days, there’s everything from friendship dynamics to school exams to contend with. That’s all on top of massive growth spurts and hormonal changes. So what role does teenage nutrition play and can a healthy diet help make adolescence any less of a rollercoaster?

Nutritional research involving under 18s is particularly difficult because studies involve a higher level of consent compared to studying adults, plus children begin puberty at different ages and their needs are constantly changing so the picture is incredibly complex with lots of moving variables. Recently, a World Health Organisation report made a strong case for investing in nutrition services as part of a comprehensive package of school health services. In 2022, an international team of adult health scientists outlined the importance of schools to improve adolescent nutrition, and mitigate a growing epidemic of malnutrition – that covers everything from undernutrition and anaemia to obesity . The paper, published in the British Medical Journal, outlines that ‘unhealthy diets are among the health risks established in adolescence that contribute to an estimated 70% of preventable deaths from non-communicable diseases in adults’.

“The impact of puberty is massive for teenagers,” says Aisling Pigott, a Cardiff-based Registered Dietitian who would love to see more research in this area. “It’s not that the nutritional guidelines change, but they’re especially important during the adolescent years.”

Different nutritional needs for boys and girls

The teenage years are a time of rapid bone and muscle growth which is demanding in terms of both nutrients and energy. Relative to their body weight, adolescents have got high energy needs, explains Pigott: “Due to the fact that they’re growing rapidly, developing and learning quickly, energy needs are not necessarily the same as an old lady or a grown adult. If adolescents are not fuelling their brains well, then it can affect things like exam results and performance in school, which has other societal and economic impacts too.”

An Australian study found that 14 year olds who ate a healthier diet high in fruit and vegetables had a higher cognitive function when they were tested three years later at the age of 17, compared to those on a diet containing more takeaways, processed meats and refined foods who showed longer reaction times and higher errors in a delayed recall task.

Registered Dietitian and Spokesperson for the Association of UK Dietitians, Anna Groom points out that all children should eat a varied diet to obtain enough calcium, vitamin D, iron and vitamins A,C, and E to ensure a healthy immune system, and that the estimated average requirements (EARs) for boys and girls are typically the same until the age of seven. “Then boys have a higher energy requirement to fuel growth, and energy requirements incrementally increase each year, however this is very individual depending on growth and genetics,” says Groom, who emphasises that for sporty adolescents, recovery from training, competition or injury can also be negatively or positively affected by nutrition: “I’m often reminding young athletes they must fuel growth as well as training and recovery which is going to affect performance. Insufficient nutrition will either mean [that their] growth potential is not achieved or training will be more challenging and training gains not be met.”

Groom explains that protein requirements are similar for boys and girls until the ages of about 14-15, then boys’ increase significantly. By comparison, iron intakes are similar until the age of about 11, and then rise for girls due to impending menarche.

So it’s important to include enough protein sources in a teenager’s diet and including enough iron-rich food too, Piggott says. “The issue is that only less than 10% of people are actually meeting nutritional guidelines anyway, so this group are at particularly high risk of things like iron deficiency anaemia, especially in girls.” She adds that girls seem to suffer the consequences of low energy in terms of eating disorders and the impacts that can have on hormones and bone health, although this can have detrimental impacts on male health too, of course.

“Adolescent bones are still forming up until 23, so calcium requirements are especially important,” says Piggott who reminds her clients that a period of malnutrition during adolescence can contribute to negative health effects in later life. “We’ve seen a massive rise in eating disorders in recent years, particularly for adolescent females. If they delay puberty, or have low body weight or inadequate energy intake and, or, they have stopped their period, actually, the lack of hormones around their system means that their bones don’t form properly or won’t become as strong as they might possibly be, putting themselves at risk of future bone disease, such as osteoporosis.”

With the recent rise in vegan diets, Piggott points out that many people rightly supplement their milk alternatives with calcium, but often, she says, the importance of supplementing with iodine gets overlooked. Iodine plays an essential role in healthy thyroid function and production of hormones such as thyroxine: “We’ve got lots of teenage girls who are potentially future mothers in 10 years’ time that maybe aren’t getting that iodine and that can impact thyroid health. And if they conceive whilst their iodine is low, that can impact the development of the child.”

Piggott explains that most health impacts, such as risk of heart disease, stroke or dementia, are the result of a cumulative effect. “If you ate very badly for 10 years and you made a change, then you are reducing that cumulative effect. However, some things aren’t necessarily reversible, such as bone health.” By your mid-20s, your bones are as strong as they will ever be, says Piggott, so in later life, improving your diet won’t add bone strength but it can help minimise bone loss.

The power of food and good nutrition in adolescence

Food is about more than just what we eat, as Piggott points out: “Food is a centering point for people. We know that during teenage years, eating can become a bit more chaotic. Regular mealtimes and family meals might go out the window for some people…so those family connections might get lost during those years as well. The non-nutritional benefits around food can have an impact too.”

So many ultra-processed foods (UPFs), from energy drinks to protein shakes, are targeted specifically at younger generations, which Piggott considers very unethical. “Teenagers are often exposed to a lot of diet culture and confusing messages around food which adults have then got to unpick and teenagers can have quite black and white approaches to food, so it becomes even more complex than trying to define food as good and bad. That can also sometimes lead to restriction, binging and other complex behaviours,” she warns.

Groom acknowledges that sleep patterns often result in teenagers missing their breakfast which could mean they risk not consuming one third of the nutrients they need. In 2017, a King’s College London study found that 27% of 11-18 year old children studied missed breakfast every day and that calcium intake was significantly higher for those consuming breakfast every day. Dr Gerda Pot, senior author of the study and Lecturer in Nutritional Sciences at King’s College London explains that: “This study provides evidence that breakfast is key for parents to ensure that their children are getting the nutrition they need.”

“Couple that with often more food choice, greater independence and financial availability and that can lead to snacking throughout the day on energy dense but nutrient low choices,” says Groom who adds that teens often feel an increased peer pressure to follow trends or try the latest craze: “From experience of working with teenagers, lack of sleep has often led to increased choice of sugary snacks to ‘keep them going’ throughout the day, particularly caffeinated sugary drinks which in my opinion should be avoided. Also, being up late increases snacking…it is therefore important healthy options such as toast, crumpets, teacakes, fruit or yoghurt should be available in place of sweets, chocolate and crisps.”

Creating healthy habits is crucial and Groom recommends reducing UPFs and increasing intake of wholegrain foods as much as possible. “UPFs are often high in refined sugar and this provides no nutrition other than energy, it can lead to unwanted weight gain and increases risk of dental caries. UPFs can be high in saturated fats which can increase risk of elevated cholesterol levels increasing long term risk of heart disease. UPFs are often low in fibre – adolescent diets should include both soluble fibre (from the skin and pith of fruit and veg) and insoluble fibre (wholegrains, oats, veg, pulses) to promote good bowel health.”

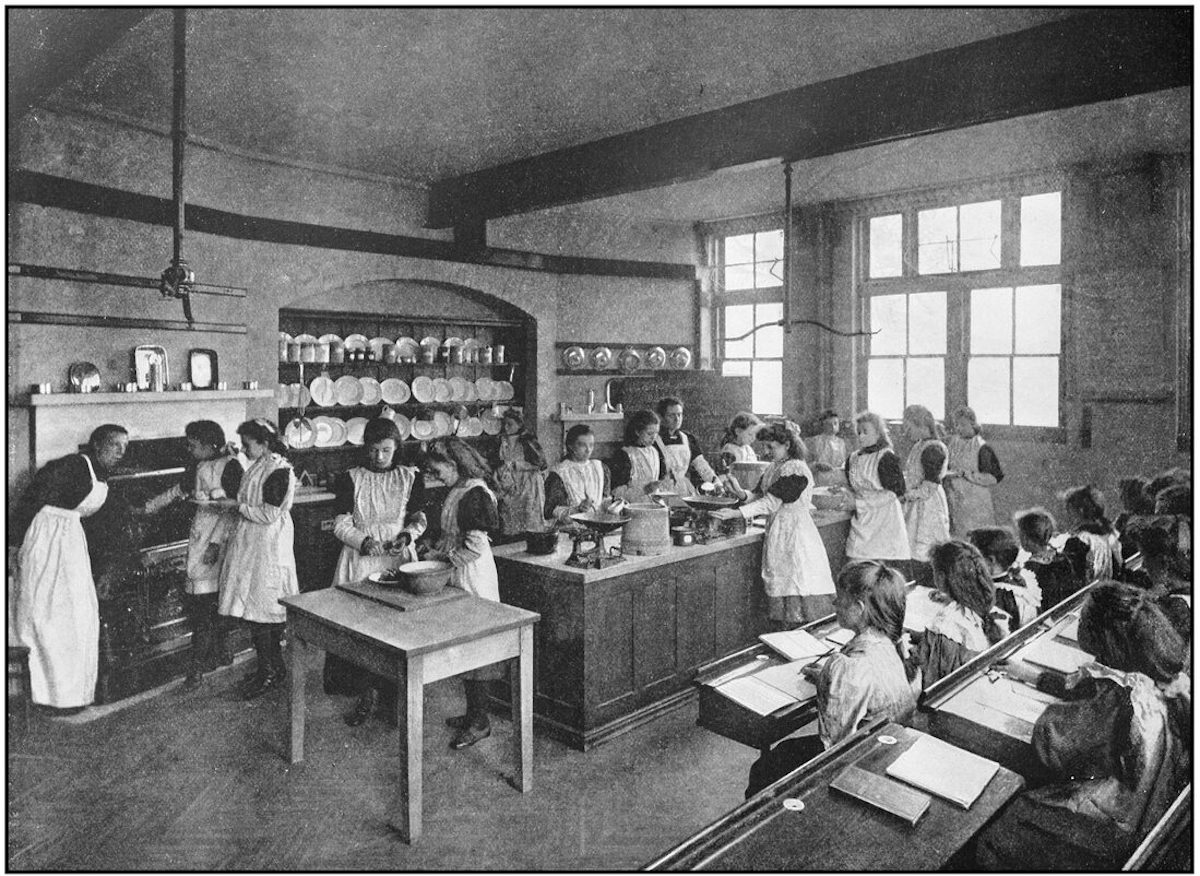

Healthy eating habits taught throughout childhood and followed as a family often continue through teenage years or at least provide a foundation, says Groom. “Teaching adolescents simple meal preparation is imperative to give them the skills to follow a healthy balanced diet,” she adds, and suggests showing teens how to plan meals to include every food group and shop on a budget.

The key is to focus on nourishment, not restriction, continues Piggott: “That’s very different to the way that teenagers talk about food, it’s very different to the way most adults talk about food as well and it’s not just parents that need to think about that. It’s the wider social network, the schools, and social media too.”