The evolution of ingredients, nutrition and consumer demand

With the abundance of comestible products on the market these days, it would be easy to think that humans have always had a large choice of food, but that isn’t the case.

Food choice is a modern concept. New ingredients, technologies, agriculture, science as well as historical events such as wars and epidemics hugely changed the food landscape in the last century.

On the other hand, many discoveries and techniques thought as modern, such as processing food, date back a million years. In fact it was Homo erectus who, by cooking the meat of its prey on an open fire, unknowingly invented what we now know as processed food.

Preservatives are also older than we might think. The Greeks, Romans and Egyptians used salt as an additive and preservative. They utilised it to dehydrate meat and fish to stop the growth and development of bacteria in their food, thus making provisions last longer – perhaps one of the very first examples of ‘prolonging shelf life’.

Fermentation to produce and preserve food and drink has been around since the Neolithic age and is still used today.

Excavated Neolithic dwellings at Skara Brae, Europe’s most complete Neolithic village

Excavated Neolithic dwellings at Skara Brae, Europe’s most complete Neolithic village

Many innovations and foods were born out of need, scarcity and population increase or decrease.

At the beginning of the eighteen hundreds, French inventor Nicolas Appert started preserving food by making hermetic bottles at La Maison Appert, his family factory. Soon after, in 1810, English merchant Peter Durand obtained the patent for a novel idea: preserving food in tin cans.

Whilst killing bacteria by heating liquids for preservation was already in use in ancient China and Japan, it was French chemist Louis Pasteur who invented the modern technique still in use today: pasteurisation. These are just three of early examples of “convenience food”.

Margarine was patented as far back as 1869. Hippolyte Mèges-Mouries was tasked by Napoleon III to create a cheap substitute for butter to feed the troops in the Franco-Prussian war. Made from beef tallow and churned with milk, the spread has evolved through the years. Margarine is now made with hydrogenated vegetable oils and it’s still a hugely popular food.

The 20th century saw many great food innovations. The reality of two world wars and the 1918’s influenza pandemic shed light on the need to change the food system to keep western populations fed and in good health. New technologies, ingredients and fortified foods were developed, and the first supermarkets were born, changing the way people ate, shopped and how they viewed and demanded food.

Food production, innovation, farming and consumer demand are not going to stop evolving, but progress, evolution and a different global and political landscape means that our needs when it comes to food have changed, and will continue to do so.

I’ve spoken to Geert Maesmans, Director Research & Development, Cargill Starches, Sweeteners & Texturizers and President of The Federation of European Specialty Food Ingredients Industries and Carole Bingley, Technical Expert at RSSL and asked them how the food industry has changed in the last five decades, and what we can expect from the near future.

How do you think ingredients, diet and nutrition has changed in the last fifty years?

Geert Maesmans: If you look at the evolution of the food industry on a global scale over the last fifty years, it has changed enormously, and predominantly for the better.

Globalisation has been essential in feeding the world, as has the revolution within the biotechnology field (e.g. seed, fermentation, synthetic biology, and cell cultures) and the improvement of processes and technology.

All of these aspects have combined to enable both the creation of safe and high-quality convenience foods, as well as to ensure the increased reliable production of staples.

The rate at which the world’s population has grown, has forced farmers, as well as feed, seed and food producers, and indeed retailers, to operate at scale. In this way, it has been possible to feed almost eight billion people on a daily basis, in a pretty solid way, even as a pandemic rages.

From a product development standpoint, there has never been greater pressure to create ever more choice and products of ever better quality. This has resulted in industry shifts, such as the complete evolution of the flavour industry in recent decades, and an increased understanding of how we look at food structure aspects, and the impact they have on texture and flavour.

At the same time, the human sciences have changed. If you look at all the insights we have gained into nutrition over the last decades, it has been exceptional. There has been such a revolution in how we think about food and the link between food and health. Take the example of the revolution currently ongoing in the field of the microbiome, and the rise of pre-, pro-, syn-, and indeed postbiotics. This is just one field that is going through a vibrant purple patch.

On the market side, there has been increased fragmentation in recent years. People are becoming more adventurous and trying new things. So for example, over two billion people already eat insects around the world, and this concept is being explored by European consumers too, now that regulatory approval is beginning to take shape.

For industry, this fragmentation requires ever greater effort into mapping and understanding changes in consumer preferences, and seeing just how granular you can go when addressing these new market opportunities. So instead of having one single offering, you may have to think about how to customize your pipeline to a specific demographic group, or in line with local preferences.

Caroline Bingley: Convenience has to be the top change. The widespread uptake of home freezers resulting in the growth of ready meals and prepared foods through to advances in packaging meaning that we can buy ready chopped vegetables. This has been accompanied by the rise in working women who no longer have the time to spend preparing meals. In the last few years there has been some backlash with many of these convenient products being described as high processed and low in nutritional quality, however, they definitely play a role in our busy lives.

What are the challenges that the food industry has faced and is still facing?

GM: Overall we have made huge progress globally. The gains that we have made in overcoming undernourishment have been significant, despite the simultaneous explosion in the global population. But we are not there yet.

Despite all that has been achieved over the last fifty years, the two basic challenges are still there: the increasing “divide” between the “haves” and the “have nots”; and the quest to find the right balance in our diets.

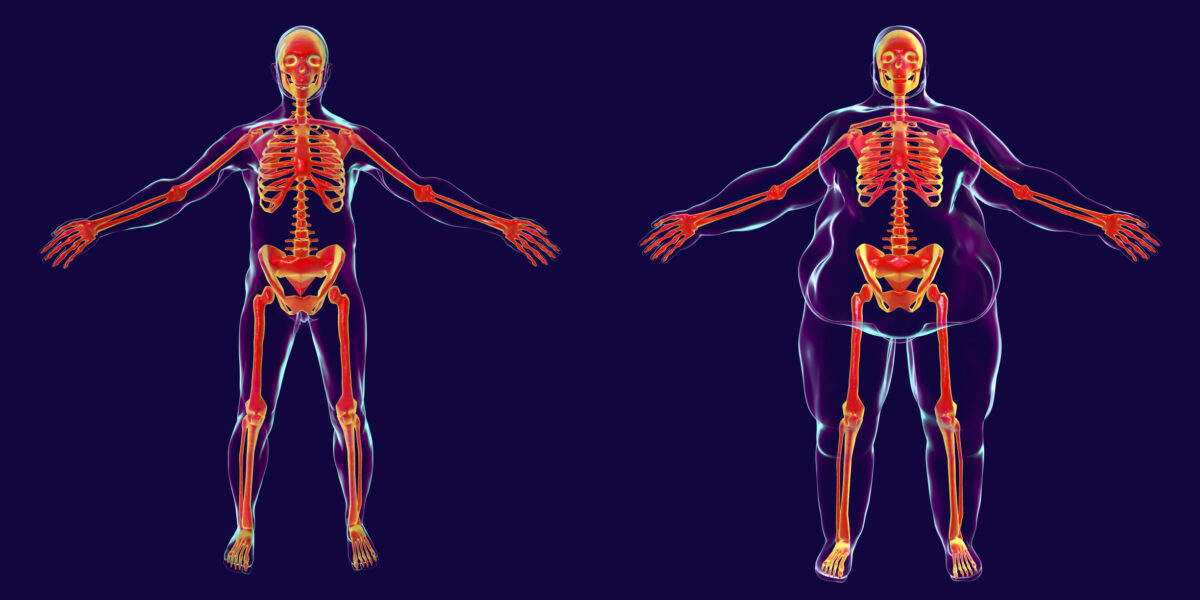

We still have around 700 million people on the planet who are undernourished. Their demands on quantity, safety, quality and diversity, are completely different, than those of the two billion people who are overnourished.

Previously, the issue of malnutrition was seen across national borders. But now you even see those discrepancies within wealthy countries and regions.

Following decades of decline, the prevalence of undernourishment is now unfortunately increasing again; the lack of diversity in the diet is contributing to that.

The issue of balance is very important too. While we may well have a better understanding of what “good nutrition” is and what constitutes “healthier eating”, together with a “healthier, more active lifestyle”; putting it into practice is an entirely different matter. As a result, obesity numbers have literally ballooned in recent years; a trend that is now likely to have been further exasperated by the lockdown. At the same time, the prevalence of eating disorders (e.g. anorexia and bulimia) is also increasing in the western world.

At a more macro level, if you look at (the UN) Sustainable Development Goals, we are making gains in terms of nutrition and quality of life, but there is room for improvement when it comes to sustaining the industry, and thereby humanity at large. Business as usual can’t sustainably feed a growing population. We simply cannot continue to use the same techniques and technologies as we have done for the last fifty years. It is a call for action, for us as an industry to continue to innovate at both a technological and operational level.

Do you think consumers are more demanding these days when it comes to food?

GM: Overall I think so. There is strong fragmentation happening, particularly in western markets, where an ever more diverse range of foods, greater convenience offerings, and more and more consumption occasions exists. This is driving industry innovation in product formats, availability, stability, and preferences.

There is a luxury dimension to this demanding nature. Today’s consumers will no longer accept eating the same meal several days in a row; they expect to always be able to enjoy a diversified, wholesome and nutritious diet. They want to have something that pleases them at whatever consumption moment they require. And with the availability of new food experiences, thanks to increased global travel, consumers look to replicate those exciting experiences at home.

Within industry, we understand that there is a paradox to these demands. On the one hand, consumers are becoming more demanding. On the other, there are fewer people actually involved in the food value chain. It appears that the less we have to roll up our sleeves, the more we expect.

I think that as food ingredients suppliers, we will need to accept more fragmentation and granularity. This will present a challenge to the food industry in offering a diverse range of ingredients supplies globally, wherever, and whenever they are needed.

In terms of consumer trends, what do you think consumers expect these days from ingredients and new products?

GM: The calls for health and sustainability are becoming increasingly vocal, whereas the demands for taste and texture have evolved from differentiators to tablestakes.

There’s no discussion any more these days about the qualifiers of food safety, security, availability and affordability. These are all a given. Furthermore, the basic emotional needs associated with food (according to latest research by Cargill’s Starches, Sweeteners & Texturizers business, consumers named pleasure, health, convenience and social responsibility in terms of food perceptions and associations), have not changed that much either.

The notion of eating together and having a good time, is still there. But there are some specifics around label-friendliness and health that are becoming more prevalent, depending on where you live, your income, and your social status.

The clean label trend encompasses both. It is partly driven by fear, in quelling some of the concerns that people have, around ingredients they do not recognize from their kitchen cupboard. In effect, what people are looking for is ingredients that deliver the same functionality but don’t actually want to see that it’s there: “invisible ingredients.” For example, you could say that the future of texture is “no texturants.” Instead you create texture in situ, like the kneading of the dough that creates the full network of the gluten and thereby gives you the full texture of the bread. But it goes as far back as your grandma using carrot or pumpkin to texturize a soup, or indeed using an egg rather than an emulsifier in a bakery product. The ingredient industry is responding to this need by providing “less refined” solutions, as well as functional flours, proteins and antioxidants. This does all create interesting challenges and new dialogues with regulators.

The other major trend here is driven by health, and relates to making conscious choices for both your own and the planet’s health. The sustainability aspect of this could involve going all the way to local short supply chains, farmers’ markets, and growing your own vegetables in your garden.

In terms of ingredients and new product development, what we can expect in the next five to ten years?

CB: I think that the clean label trend will continue to be very important to consumers and we will see more clean label ingredients which can address nutritional issues such as sugar/fat reduction or fortification with vitamins and minerals. I also think that fermentation techniques will be increasingly important in the development of new ingredients such as proteins – these techniques give opportunities for innovation whilst having good sustainability credentials.

GM: In the next five years, you are going to see the continuation of the routes that have been chosen now. Within the technology track, you will see the acceleration of plant proteins, fibres, more vegetable based products and the continued development of dairy protein via fermentation, cell cultured meats etc.

At a consumer product level, we’ll continue to explore the 3D printing of foods, the personalization of nutrition based on our genetic profile, microbiome, and fitness state. It’s about “more technology inside our food.”

Concurrently, you will see the increased need within society to have more nutritious and sustainable products that are based on less refined ingredients and foods, that you create yourself, and which are driven by transparency and familiarity. Here it’s about “even less technology inside our food.”

Those two trends will need to converge within both an economical and regulatory framework that allows it. You will see more fragmentation between those that want high tech foods, and those that want low tech foods that you prepare yourself from basic ingredients. In fact, it may well be that the same people seeking out ultra-convenient, high quality fast food during the week, will purchase their ingredients from the farmer’s market, and enjoy a slow-cooking family moment at the weekend.

What ingredients and products that were popular in the last five decades are no longer used in food manufacturing or have disappeared from the supermarket shelves and why do you think that is?

CB: I think that artificial colours and flavours are the most obvious example. Consumers are increasingly wary of anything described as artificial and the Southampton study (the 2007 research that found a link between hyperactivity in children and food additives) was really the nail in the coffin for artificial colours. However, they do have good stability through processing and shelf life, are usually lower in cost than natural versions and the search for a natural blue colour has been challenging.

During your career, have you ever marvelled at the popularity or unpopularity of an ingredient that you thought would never take off or were surprised it did?

CB: I think that it takes some time for ingredients to find their niche. Inulin would be a good example. It came to market a long time ago but has only found commercial success in the past few years. It is a useful ingredient for sugar reduction in food products, is a prebiotic and can be described as clean label. It isn’t a low cost ingredient but the push for sugar reduction has meant that manufacturers are now using it in many products. So, I’m not surprised by its popularity I was just surprised by how long it took!

What are the factors that influence the popularity of a specific ingredient?

CB: This does vary depending on the ingredient but I would say price, functionality and labelling (e.g. can it be described as ‘clean label’?).

What ingredients do you think will never lose their popularity with consumers?

GM: “Never” is a long time – so it’s impossible to make long term predictions. Having said that, there are certainly aspects that can guide the likely trends.

There are really two dimensions that influence consumer preferences. On the one hand, upbringing has an enormous impact on what you are accustomed to eating; whether this relates to branded or unbranded ingredients and products. The ones that your parents consumed, are often those that you will continue to use yourself in the future.

On the other hand, when it comes to the newer and trendier foods, they are very much driven by your identity, and who you want to be.

For example, my daughter has a very different outlook than my son, which drives quite a few of her eating and cooking choices. As a result of her vegan and vegetarian choices, she will buy different ingredients than he would purchase. It has certainly enriched our dinner table conversations!

So from one side, there is a whole discussion around health. Secondly, sustainability is high on the agenda. But perhaps most importantly, it is about the emotional associations that people have with the foods they consume. For some, food is merely a nourishment tool, but for others it forms part of their identity, and preferences that may well stay with them for a lifetime.